Type 2 Diabetes Exercise Impact Calculator

Estimated Improvements

Enter your details and click "Calculate" to see estimated improvements in your diabetes management.

Exercise Benefits Overview

Type2 Diabetes is a chronic condition where the body either resists insulin or doesn’t produce enough, causing elevated blood glucose levels. While medication does a lot of the heavy lifting, scientists and clinicians agree that exercise a regular pattern of physical movement that raises heart rate and uses muscle groups can shift the needle dramatically. If you’ve ever wondered whether a brisk walk could replace a pill, the answer is yes-though not completely, and not without a plan.

Why Your Muscles Matter More Than You Think

When you move, your muscles become insulin‑hungry. This is called insulin sensitivity the ability of cells to respond to insulin and pull glucose from the bloodstream. A single 30‑minute walk can boost that sensitivity by 20‑30% for up to 24hours. Think of it as a temporary upgrade to the doorbell that tells glucose “you’re welcome home”. The more often you press that button, the less work the pancreas has to do.

Blood Sugar Control in Real Numbers

Researchers at the University of Exeter tracked 200 adults with Type2 Diabetes who added 150minutes of moderate aerobic activity each week. After six months, average fasting glucose fell from 9.2mmol/L to 7.1mmol/L, and Hemoglobin A1C a blood test that reflects average glucose over the past 2‑3 months dropped 0.8percentage points-a change comparable to adding a second diabetes medication.

Cardiovascular Health: The Hidden Bonus

People with Type2 Diabetes face a two‑fold higher risk of heart disease. Regular aerobic exercise reduces blood pressure, improves lipid profiles, and lowers inflammation. A meta‑analysis published in the British Medical Journal showed a 15% reduction in cardiovascular events for participants who met the Physical Activity Guidelines 150minutes of moderate‑intensity activity per week, plus two strength sessions. In other words, moving your body attacks the two biggest killers for diabetics at the same time.

Weight Management Without Starving

Weight loss is often touted as the magic bullet for diabetes. While shedding excess pounds does improve insulin action, exercise offers a calorie‑burning advantage that doesn’t rely on strict dieting. Resistance training, for example, builds lean muscle, which burns more calories at rest than fat. In a 12‑week trial, participants who added two 45‑minute strength sessions kept their weight stable but saw a 12% drop in insulin resistance, measured by the HOMA‑IR index.

Combining Exercise With Medication

Most patients are already on Metformin the first‑line oral drug that lowers liver glucose production. Studies show that the glucose‑lowering effect of Metformin nearly doubles when paired with regular aerobic activity. The synergy works because Metformin improves the muscle’s ability to take up glucose, and exercise tells those muscles to open the doors wider. The result? Lower doses, fewer side‑effects, and a smoother blood‑sugar curve.

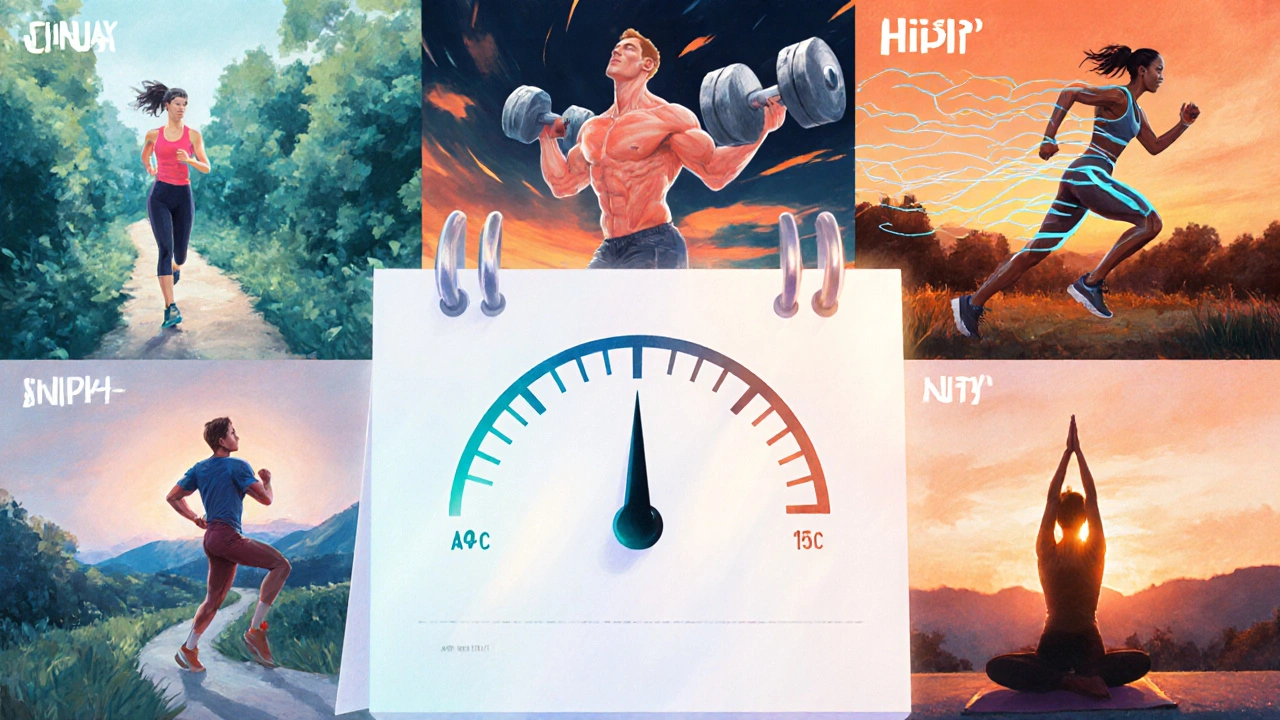

Choosing the Right Kind of Exercise

| Exercise Type | Primary Benefit | Suggested Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Aerobic (brisk walking, cycling) | Improves insulin sensitivity, lowers fasting glucose | 150min/week moderate or 75min/week vigorous |

| Resistance (weight machines, body‑weight) | Builds lean muscle, boosts resting metabolism | 2-3 sessions/week, 8-12 reps per set |

| HIIT (short bursts, 30‑second sprints) | Rapid A1C reduction, enhances cardiovascular fitness | 1-2 sessions/week, 10‑minute total work |

| Flexibility/Balance (yoga, tai chi) | Reduces stress hormones that raise glucose | 3-4 sessions/week, 20min each |

Mixing these categories gives you the best of every world. A typical week might look like three brisk walks, two resistance days, and a short HIIT burst on the weekend.

Practical Tips to Stay Consistent

- Schedule workouts like doctor appointments-write them in your calendar.

- Start with a 10‑minute walk after dinner; the habit builds faster than a marathon plan.

- Use a wearable or phone app to track steps and heart rate; data keeps you honest.

- Pair activity with a friend or a local walking group; social accountability trumps willpower.

- Check blood glucose before and after new activities to see immediate effects and avoid hypoglycemia.

Remember, the goal isn’t perfection; it’s steady progress. Even a 5% increase in weekly activity can shave 0.3% off A1C over three months.

Key Takeaways

- Exercise boosts exercise and type 2 diabetes outcomes by enhancing insulin sensitivity and lowering glucose.

- Both aerobic and resistance training are essential; aim for at least 150minutes of moderate cardio plus two strength sessions each week.

- Combining movement with medication like Metformin can halve the required drug dose.

- Track progress with simple tools-step counters, glucose logs, or a calendar.

- Consistency beats intensity; small daily habits create lasting metabolic changes.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I exercise if I’m on insulin?

Yes, but monitor your blood sugar closely. Physical activity can cause glucose to drop, so test before and after workouts and adjust insulin doses if needed. Many clinicians recommend reducing rapid‑acting insulin by 10‑20% on active days.

Is walking enough or do I need a gym?

Walking meets the aerobic portion of the guidelines and delivers measurable glucose benefits. Adding a couple of resistance sessions-using dumbbells, resistance bands, or body‑weight moves-completes the prescription. A gym isn’t mandatory, just variety.

How quickly will I see changes in my A1C?

A1C reflects average glucose over roughly three months. Most studies report a 0.5‑1.0% drop after 12‑16 weeks of consistent moderate exercise combined with stable medication.

What if I have joint pain?

Low‑impact activities like swimming, cycling, or elliptical training reduce joint stress while still boosting insulin sensitivity. Incorporating flexibility work (yoga, tai chi) can also ease pain and improve glucose control.

Should I fast before exercising?

Fasting isn’t required and may increase hypoglycemia risk, especially if you use insulin or sulfonylureas. A small carbohydrate snack (e.g., a banana) 30minutes before a workout is a safe default.

James McCracken

October 5, 2025 AT 13:50One could argue that the glorified love‑letter to exercise in the post is nothing more than a convenient narrative for the pharmaceutical industry, cloaking the true complexity of metabolic regulation in a simplistic "walk more, insulin less" mantra. While the data are solid, the notion that a brisk stroll can replace a pill borders on romanticism rather than reality. The human body, after all, is a tapestry of hormonal interplay, genetic predisposition, and lifestyle context that no single activity can wholly rewrite. A more nuanced view would acknowledge that exercise is a powerful adjunct, not a panacea, and that the social determinants of health often dictate who can even afford the time to move. In that light, the article could benefit from a deeper dive into the socioeconomic barriers that temper the lofty claims presented.

Evelyn XCII

October 5, 2025 AT 14:00Wow, because reading a blog post totally cured my diabetes, right?

Suzanne Podany

October 5, 2025 AT 14:10Hey everyone, just wanted to add a friendly reminder that no matter where you start, consistency beats intensity every time. Even a 10‑minute walk after dinner can build a habit that snowballs into the 150‑minute weekly goal. Think of your body as a community garden; regular watering (exercise) nurtures the soil (muscles) so they can absorb nutrients (glucose) more efficiently. Pairing gentle strength moves-like body‑weight squats or resistance band rows-with your cardio can amplify insulin sensitivity without overwhelming your schedule. Remember, every step is a victory, and sharing your milestones with a buddy or online group can keep motivation high. Keep moving, stay safe, and celebrate the small wins-you’ve got this!

Nina Vera

October 5, 2025 AT 14:20Oh my gosh, the drama of a simple walk turning into a life‑changing saga! I can see it now: sunrise, sweaty heroics, the crowds gasping as my glucose levels tumble dramatically. Who needs a Netflix series when you have the epic tale of the treadmill triumph? Let’s all throw confetti on our sneakers and march to the beat of our own dazzling A1C drops.

Seriously, though, keep the hype alive-because nothing fuels a community like a little theatrical flair!

Christopher Stanford

October 5, 2025 AT 14:30This article is riddled with oversimplifications that could mislead patients. While the stats are appealing, they hide the fact that not everyone can sustain 150 minutes of aerobic activity due to joint issues, work constraints, or simply lack of safe environments. The claim that "exercise can halve the required drug dose" ignores the variability in individual response and the need for medical supervision. Additionally, the piece fails to address the potential for hypoglycemia in insulin‑treated users who jump into intense regimens without proper guidance. In short, the post sells a one‑size‑fits‑all solution while glossing over the real-world challenges.

Steve Ellis

October 5, 2025 AT 14:40Great points raised, and I’d like to build on them with a supportive note: anyone feeling overwhelmed, try breaking the 150‑minute goal into three 10‑minute walks spread throughout the day. Those tiny victories add up, and you’ll notice the confidence boost before you know it. Remember, the muscles you strengthen today are the allies that will help you conquer tomorrow’s challenges. Keep encouraging each other, share your progress, and celebrate every step forward-your future self will thank you.

Jennifer Brenko

October 5, 2025 AT 14:50From a Canadian perspective, it is imperative to underscore that the United States' emphasis on high‑intensity exercise overlooks the cultural preference for moderate, outdoor activities such as cycling and hockey‑related conditioning. While the data cited are valid, they fail to consider that our northern climate necessitates seasonally adjusted regimens, which can influence adherence and outcomes. Moreover, the article’s assertion that exercise can substantially reduce medication dosages should be tempered with caution, given the regulatory differences between our health systems. A more balanced approach that integrates cross‑border research would enhance the credibility of the recommendations.

Harold Godínez

October 5, 2025 AT 15:00Just a quick heads‑up: the term "Aerobic" is generally capitalized in most style guides when used as a heading, but not in the middle of sentences. Also, watch out for missing commas after introductory phrases like "In short,". Small tweaks can make the piece look polished and professional.

Sunil Kamle

October 5, 2025 AT 15:10It is with the utmost formality that I commend the authors for presenting a comprehensive overview of exercise benefits. Yet, one cannot help but note the subtle irony in urging the very audience that struggles with time constraints to engage in additional activities. Nevertheless, the data remain persuasive, and the recommendations, while ambitious, are grounded in solid evidence.

Michael Weber

October 5, 2025 AT 15:20Imagine, if you will, the human body as a vast library of biochemical scrolls, each gene and enzyme a vellum page awaiting illumination. Exercise, then, is not merely a physical act but a deliberate re‑inscription of these texts, a hermetic ritual that rewrites the language of glucose metabolism. The article's earnest exhortations, while well‑intentioned, reduce this profound transformation to a checklist of minutes and sessions, as if the soul of metabolic regulation could be captured in a spreadsheet.

Consider the paradox: we are urged to move more to become less dependent on pharmacologic agents, yet many of us are shackled by the very social structures that limit free movement-long commutes, sedentary occupations, and the omnipresent lure of digital distraction. To proclaim that a 150‑minute weekly walk can halve medication dosages is to ignore the dialectic between agency and environment.

Furthermore, the emphasis on quantitative goals neglects the qualitative experience of embodiment. The sensation of muscles fatigued yet resilient, the rhythmic cadence of breath matching heartbeats, these are not merely data points but narratives of resilience that cannot be distilled into percentages.

In clinical practice, the psychologist often reminds us that patient adherence is less a function of knowledge than of identity. When a person internalizes the mantra "I am an active individual," the metabolic benefits accrue as a byproduct of that self‑concept. The article would benefit from exploring how cultural narratives shape the willingness to embrace exercise.

Lastly, the interplay between exercise and medication is not a linear equation but a complex system of feedback loops. Metformin, for instance, sensitizes muscle cells, thereby amplifying the glucose‑uptake signal generated by contraction. Yet this synergy is contingent upon timing, dosage, and the individual's baseline insulin resistance.

In sum, while the pragmatic advice offered is valuable, it stands on a foundation that demands deeper philosophical reflection. Let us honor the intricate dance between movement and metabolism, recognizing that each step taken is both a physiological event and a symbolic affirmation of agency.